More Control Flow Tools

As well as the while statement just introduced, Python uses a few more that we will encounter in this chapter.

if Statements

Perhaps the most well-known statement type is the if statement. For example:

>>> x = int(input("Please enter an integer: "))

Please enter an integer: 42

>>> if x < 0:

... x = 0

... print('Negative changed to zero')

... elif x == 0:

... print('Zero')

... elif x == 1:

... print('Single')

... else:

... print('More')

...

MoreThere can be zero or more elif parts, and the else part is optional. The keyword ‘elif’ is short for ‘else if’, and is useful to avoid excessive indentation. An if … elif … elif … sequence is a substitute for the switch or case statements found in other languages.

Python 中没有

switch-case语句,而是用if-elif-else语句代替之。

If you’re comparing the same value to several constants, or checking for specific types or attributes, you may also find the match statement useful. For more details see match Statements .

for Statements

The for statement in Python differs a bit from what you may be used to in C or Pascal. Rather than always iterating over an arithmetic progression of numbers (like in Pascal), or giving the user the ability to define both the iteration step and halting condition (as C), Python’s for statement iterates over the items of any sequence (a list or a string), in the order that they appear in the sequence. For example (no pun intended):

对于

for循环,与 Pascal 中对数字进行算术级数的迭代、C 中让用户定义迭代步长和停止条件不同,Python 按照各项出现在序列(如list、string 中)的顺序进行迭代。

>>> # Measure some strings:

... words = ['cat', 'window', 'defenestrate']

>>> for w in words:

... print(w, len(w))

...

cat 3

window 6

defenestrate 12

Code that modifies a collection while iterating over that same collection can be tricky to get right. Instead, it is usually more straight-forward to loop over a copy of the collection or to create a new collection:

在修改集合的同时迭代同一集合的代码可能会很难处理(试想,迭代到第二个项时将其删除,那么下一个迭代的项是什么?)。 所以,更推荐循环遍历集合的副本或创建一个新的集合。

# Create a sample collection

users = {'Hans': 'active', 'Éléonore': 'inactive', '景太郎': 'active'}

# Strategy: Iterate over a copy

for user, status in users.copy().items():

if status == 'inactive':

del users[user]

# Strategy: Create a new collection

active_users = {}

for user, status in users.items():

if status == 'active':

active_users[user] = statusThe range Function

If you do need to iterate over a sequence of numbers, the built-in function range comes in handy1. It generates arithmetic progressions:

如果确实需要遍历一串数字,Python 的内置函数

range就可以实现,并且可以根据参数调整起始、结束、步长。

>>> for i in range(5):

... print(i)

...

0

1

2

3

4

The given end point is never part of the generated sequence; range(10) generates 10 values, the legal indices for items of a sequence of length 10. It is possible to let the range start at another number, or to specify a different increment (even negative; sometimes this is called the ‘step’):

步长是

range的第三个参数,默认为 1,也可以设置为其它数(包括负数)。 并且仍然是左闭右开(顺序上的,而不是数值大小上的)的规则。

>>> list(range(5, 10))

[5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

>>> list(range(0, 10, 3))

[0, 3, 6, 9]

>>> list(range(-10, -100, -30))

[-10, -40, -70]To iterate over the indices of a sequence, you can combine range and len as follows:

>>> a = ['Mary', 'had', 'a', 'little', 'lamb']

>>> for i in range(len(a)):

... print(i, a[i])

...

0 Mary

1 had

2 a

3 little

4 lamb

In most such cases, however, it is convenient to use the enumerate() function, see Looping Techniques.

不过除了上面类似 C 的遍历列表的方法外,在 Python 中更推荐使用

enumerate函数来实现。

A strange thing happens if you just print a range:

>>> range(10)

range(0, 10)

In many ways the object returned by range behaves as if it is a list, but in fact it isn’t. It is an object which returns the successive items of the desired sequence when you iterate over it, but it doesn’t really make the list, thus saving space.

从很多方面来看,

range()返回的对象就像是一个列表,但事实上它并不是。它是一个对象,当你遍历它时,它会返回所需的序列的连续项,但它并不真正构成列表,因此节省了空间。

We say such an object is iterable, that is, suitable as a target for functions and constructs that expect something from which they can obtain successive items until the supply is exhausted. We have seen that the for statement is such a construct, while an example of a function that takes an iterable is sum():

我们将这样的对象称为 可迭代的 ,意即它适合作为函数和代码结构的作用目标,函数和结构体期望从中获得连续的项并直到遍历结束。

我们讨论的

for循环就是这样的代码结构,而使用可迭代对象的函数的一个例子就是sum函数:

>>> sum(range(4)) # 0 + 1 + 2 + 3

6

Later we will see more functions that return iterables and take iterables as arguments. In chapter Data Structures, we will discuss in more detail about list().

break and continue Statements, and else Clauses on Loops

The break statement breaks out of the innermost enclosing for or while loop.

A for or while loop can include an else clause. In a for loop, the else clause is executed after the loop reaches its final iteration. In a while loop, it’s executed after the loop’s condition becomes false. In either kind of loop, the else clause is not executed if the loop was terminated by a break.

This is exemplified in the following for loop, which searches for prime numbers:

break语句可以跳出最内层的for或while的循环。而

for和while循环可已包含else子句,

- 在

for循环中else子句在循环到达最后一次迭代后执行- 而在

while循环中else子句在循环条件变为 false 后执行。无论哪种循环,如果循环被

break提前终止,那么之后的else子句都不会执行。

>>> for n in range(2, 10):

... for x in range(2, n):

... if n % x == 0:

... print(n, 'equals', x, '*', n//x)

... break

... else:

... # loop fell through without finding a factor

... print(n, 'is a prime number')

...

2 is a prime number

3 is a prime number

4 equals 2 * 2

5 is a prime number

6 equals 2 * 3

7 is a prime number

8 equals 2 * 4

9 equals 3 * 3(Yes, this is the correct code. Look closely: the else clause belongs to the for loop, not the if statement.)

When used with a loop, the else clause has more in common with the else clause of a try statement than it does with that of if statements: a try statement’s else clause runs when no exception occurs, and a loop’s else clause runs when no break occurs. For more on the try statement and exceptions, see Handling Exceptions.

loop-else其实与try-else这个语句块比较相似,try-else在没有捕获到异常时会运行else中的代码;而loop-else会在没有break跳出循环时运行else中的代码。

The continue statement, also borrowed from C, continues with the next iteration of the loop:

continue语句与 C 中的语义一致。

>>> for num in range(2, 10):

... if num % 2 == 0:

... print("Found an even number", num)

... continue

... print("Found an odd number", num)

...

Found an even number 2

Found an odd number 3

Found an even number 4

Found an odd number 5

Found an even number 6

Found an odd number 7

Found an even number 8

Found an odd number 9pass Statements

The pass statement does nothing. It can be used when a statement is required syntactically but the program requires no action. For example:

pass语句只是为了使代码块在语法上合法,即让这个代码块为空,既不会报错,也不会执行任何操作。

>>> while True:

... pass # Busy-wait for keyboard interrupt (Ctrl+C)

...

This is commonly used for creating minimal classes:

- 因此通常用来创建一些小型的类。

>>> class MyEmptyClass:

... pass

...

Another place pass can be used is as a place-holder for a function or conditional body when you are working on new code, allowing you to keep thinking at a more abstract level. The pass is silently ignored:

2. 或者在函数或状态块中放置,暂时搁置这个地方的代码编写,专注自己的思路,等之后有时间再来补充之。

>>> def initlog(*args):

... pass # Remember to implement this!

...

match Statements

A match statement takes an expression and compares its value to successive patterns given as one or more case blocks. This is superficially similar to a switch statement in C, Java or JavaScript (and many other languages), but it’s more similar to pattern matching in languages like Rust or Haskell. Only the first pattern that matches gets executed and it can also extract components (sequence elements or object attributes) from the value into variables.

match语句使用一个表达式,并将其值与作为一个或多个 case 块给出的连续模式进行比较。这表面上类似于 C、Java 或 JavaScript(以及许多其他语言)中的 switch 语句,但更类似于 Rust 或 Haskell 等语言中的模式匹配。只有第一个匹配到的模式才会被执行,它还可以从变量值中提取成分(序列元素或对象属性)。

The simplest form compares a subject value against one or more literals:

def http_error(status):

match status:

case 400:

return "Bad request"

case 404:

return "Not found"

case 418:

return "I'm a teapot"

case _:

return "Something's wrong with the internet"

Note the last block: the “variable name” _ acts as a wildcard2 and never fails to match. If no case matches, none of the branches is executed.

最后一个 case 块中的变量

_扮演了通配符的角色,它永远不会匹配失败。在

match中如果没有匹配情况(即_没有设置),则不会执行任何分支。

You can combine several literals in a single pattern using | (“or”):

可以在一个 case 中组合多个匹配值,使用

|运算符(意为“or”)。

case 401 | 403 | 404:

return "Not allowed"

Patterns can look like unpacking assignments3, and can be used to bind variables:

case 要匹配的模式看起来像解包赋值——可以用于绑定变量。

# point is an (x, y) tuple

match point:

case (0, 0):

print("Origin")

case (0, y):

print(f"Y={y}")

case (x, 0):

print(f"X={x}")

case (x, y):

print(f"X={x}, Y={y}")

case _:

raise ValueError("Not a point")

Study that one carefully! The first pattern has two literals, and can be thought of as an extension of the literal pattern shown above. But the next two patterns combine a literal and a variable, and the variable binds a value from the subject (point). The fourth pattern captures two values, which makes it conceptually similar to the unpacking assignment (x, y) = point.

If you are using classes to structure your data you can use the class name followed by an argument list resembling a constructor, but with the ability to capture attributes into variables:

如果使用类来构造数据,则可以使用类名,后面跟一个类似构造函数的参数列表,然后可以将属性捕获到变量中:

class Point:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def where_is(point):

match point:

case Point(x=0, y=0):

print("Origin")

case Point(x=0, y=y):

print(f"Y={y}")

case Point(x=x, y=0):

print(f"X={x}")

case Point():

print("Somewhere else")

case _:

print("Not a point")

You can use positional parameters with some builtin classes that provide an ordering for their attributes (e.g. dataclasses). You can also define a specific position for attributes in patterns by setting the __match_args__ special attribute in your classes. If it’s set to (“x”, “y”), the following patterns are all equivalent (and all bind the y attribute to the var variable):

有些内置类(如数据类)提供了属性排序,您可以在这些类中使用位置参数。

你还可以通过在类中设置

__match_args__特殊属性,为模式中的属性定义特定的位置。如果将其设置为(“x”, “y”),以下模式都是等价的(并且都将 y 属性绑定到 var 变量):

Point(1, var)

Point(1, y=var)

Point(x=1, y=var)

Point(y=var, x=1)

A recommended way to read patterns is to look at them as an extended form of what you would put on the left of an assignment, to understand which variables would be set to what. Only the standalone names (like var above) are assigned to by a match statement. Dotted names (like foo.bar), attribute names (the x= and y= above) or class names (recognized by the ” (…)” next to them like Point above) are never assigned to.

阅读模式的推荐方法是将其视为赋值左边的扩展形式,以了解哪些变量将被设置为哪些变量。只有独立的名称(如上文的 var)才会被匹配语句赋值。点名(如 foo. bar)、属性名(如上文的

x=和y=)或类名(如上文的 Point,旁边有” (…)”)永远不会被赋值。

Patterns can be arbitrarily nested. For example, if we have a short list of Points, with __match_args__ added, we could match it like this:

模式可以任意嵌套。例如下面代码中嵌套入列表之中。

class Point:

__match_args__ = ('x', 'y')

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

match points:

case []:

print("No points")

case [Point(0, 0)]:

print("The origin")

case [Point(x, y)]:

print(f"Single point {x}, {y}")

case [Point(0, y1), Point(0, y2)]:

print(f"Two on the Y axis at {y1}, {y2}")

case _:

print("Something else")We can add an if clause to a pattern, known as a “guard”. If the guard is false, match goes on to try the next case block. Note that value capture happens before the guard is evaluated:

可以在模式中添加

if子句,称之为“哨兵”。如果哨兵是false,那么就跳过当前模式并检查下一个模式。不过需要注意,解包赋值在哨兵检查之前就会完成。

match point:

case Point(x, y) if x == y:

print(f"Y=X at {x}")

case Point(x, y):

print(f"Not on the diagonal")

Several other key features of this statement:

- Like unpacking assignments, tuple and list patterns have exactly the same meaning and actually match arbitrary sequences. An important exception is that they don’t match iterators or strings.

与解包赋值一样,元组模式和列表模式具有完全相同的含义,实际上可以匹配任意序列。一个重要的例外是,它们不能匹配迭代器或字符串。

- Sequence patterns support extended unpacking:

[x, y, *rest]and(x, y, *rest)work similar to unpacking assignments. The name after*may also be_, so(x, y, *_)matches a sequence of at least two items without binding the remaining items.

序列模式支持扩展解包:

[x, y, *rest]和(x, y, *rest)的作用类似于解包赋值。* 后面的名称也可以是_,因此(x, y, *_)可以匹配至少两个项目的序列,而不绑定其余项。

- Mapping patterns:

{"bandwidth": b, "latency": l}captures the"bandwidth"and"latency"values from a dictionary. Unlike sequence patterns, extra keys are ignored. An unpacking like**restis also supported. (But**_would be redundant, so it is not allowed.)

在字典中,模式匹配将会检查 key。 与序列模式不同,额外的键key 会被忽略。 支持像

**rest这样的解包,但**_是多余的,因此不允许使用。

- Subpatterns may be captured using the

askeyword:

case (Point(x1, y1), Point(x2, y2) as p2): ...

will capture the second element of the input as p2 (as long as the input is a sequence of two points)

可使用

as关键字捕捉子模式。 上面的例子中将捕捉输入的第二个元素作为p2。

- Most literals are compared by equality, however the singletons

True,FalseandNoneare compared by identity.

大多数常量都是通过相等来比较的,而单字 True、False 和 None 则是通过一致来比较的。

- Patterns may use named constants. These must be dotted names to prevent them from being interpreted as capture variable:

from enum import Enum

class Color(Enum):

RED = 'red'

GREEN = 'green'

BLUE = 'blue'

color = Color(input("Enter your choice of 'red', 'blue' or 'green': "))

match color:

case Color.RED:

print("I see red!")

case Color.GREEN:

print("Grass is green")

case Color.BLUE:

print("I'm feeling the blues :(")模式可以使用命名常量。这些名称必须是带点的,以防被解释为捕获变量。

For a more detailed explanation and additional examples, you can look into PEP 636 which is written in a tutorial format.

Defining Functions

We can create a function that writes the Fibonacci series to an arbitrary boundary:

>>> def fib(n): # write Fibonacci series up to n

... """Print a Fibonacci series up to n."""

... a, b = 0, 1

... while a < n:

... print(a, end=' ')

... a, b = b, a+b

... print()

...

>>> # Now call the function we just defined:

... fib(2000)

0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377 610 987 1597The keyword def introduces a function definition. It must be followed by the function name and the parenthesized list of formal parameters. The statements that form the body of the function start at the next line, and must be indented.

The first statement of the function body can optionally be a string literal; this string literal is the function’s documentation string, or docstring. (More about docstrings can be found in the section Documentation Strings.) There are tools which use docstrings to automatically produce online or printed documentation, or to let the user interactively browse through code; it’s good practice to include docstrings in code that you write, so make a habit of it.

函数体的第一部分是可选的字符串常量——使用

"""..."""包围字符串,作为该函数的使用说明,称之为文档字符串 docstring 。 Python 中有一些工具可以使用 docstring 自动生成文档,或者在浏览诸多函数时给自己提示,因此为了代码的可读性,非常建议及时编写文档字符串。

The execution of a function introduces a new symbol table used for the local variables of the function. More precisely, all variable assignments in a function store the value in the local symbol table; whereas variable references first look in the local symbol table, then in the local symbol tables of enclosing functions, then in the global symbol table, and finally in the table of built-in names. Thus, global variables and variables of enclosing functions cannot be directly assigned a value within a function (unless, for global variables, named in a global statement, or, for variables of enclosing functions, named in a nonlocal statement), although they may be referenced.

执行一个函数会为该函数的局部变量引入一个新的符号表,更精确地说,在一个函数中所有变量的赋值都会将值存储在一个局部符号表中——当变量引用时,首先会查看局部符号表,其次在外层函数的局部符号表中查找,再次查看全局符号表,最后在 Python 内置变量的符号表中查找。

因此,尽管全局变量和外层函数的变量可以被(内层函数)引用,但是不能在函数中直接赋值(除非对全局变量使用

global语句修饰,或者对函数的内部变量用nonlocal语句修饰)。

The actual parameters (arguments) to a function call are introduced in the local symbol table of the called function when it is called; thus, arguments are passed using call by value (where the value is always an object reference, not the value of the object). 4 When a function calls another function, or calls itself recursively, a new local symbol table is created for that call.

函数调用时所传递的实参会被引入该函数的局部符号表,这样的参数传递称为 按值传递(call by value),此处的“值”是对象的引用,而不是对象本身的值。 如果 A 函数调用了 B 函数,或者递归地调用自身,那么也会为这次调用创建新的局部符号表。

A function definition associates the function name with the function object in the current symbol table. The interpreter recognizes the object pointed to by that name as a user-defined function. Other names can also point to that same function object and can also be used to access the function:

函数定义将函数名与当前符号表中的函数对象联系起来,解释器通过名字将对象识别为 用户定义函数 。

如果为函数起别名,那么也可以指向相同的函数并通过同样的方式访问。

>>> fib

<function fib at 10042ed0>

>>> f = fib

>>> f(100)

0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89

Coming from other languages, you might object that fib is not a function but a procedure since it doesn’t return a value. In fact, even functions without a return statement do return a value, albeit a rather boring one. This value is called None (it’s a built-in name). Writing the value None is normally suppressed by the interpreter if it would be the only value written. You can see it if you really want to using print():

在 Python 中,即使没有显式地返回语句来返回函数运行的结果,实际上仍然有返回值——称为

None,这是一个内置名。(这点与其它强调函数与过程之分的语言不同)如果输出的结果是

None,那么 Python 解释器通常会阻止将其输出出来;如果真的想看,那么应该使用print()函数。

>>> fib(0)

>>> print(fib(0))

None

It is simple to write a function that returns a list of the numbers of the Fibonacci series, instead of printing it:

>>> def fib2(n): # return Fibonacci series up to n

... """Return a list containing the Fibonacci series up to n."""

... result = []

... a, b = 0, 1

... while a < n:

... result.append(a) # see below

... a, b = b, a+b

... return result

...

>>> f100 = fib2(100) # call it

>>> f100 # write the result

[0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89]

This example, as usual, demonstrates some new Python features:

- The

returnstatement returns with a value from a function.returnwithout an expression argument returnsNone. Falling off the end of a function also returnsNone.

return语句从函数中返回一个值,不带表达式参数的return返回None。函数结束时也返回None。

- The statement

result.append(a)calls a method of the list objectresult. A method is a function that ‘belongs’ to an object and is namedobj.methodname, whereobjis some object (this may be an expression), andmethodnameis the name of a method that is defined by the object’s type. Different types define different methods. Methods of different types may have the same name without causing ambiguity. (It is possible to define your own object types and methods, using classes, see Classes) The methodappend()shown in the example is defined for list objects; it adds a new element at the end of the list. In this example it is equivalent toresult = result + [a], but more efficient.

fib2中对列表result的操作append(a)在 Python 中称为列表对象的 方法 。此方法是列表类所定义的,会在列表的末尾添加一个新的元素,这等价于result = result + [a],但是更加高效5。在 Python 中方法是特殊的函数,其“属于”特定对象并且通过

obj.methodname语句来调用。方法的定义取决于对象的类型,不同的对象有其不同的方法,而不同的对象也有可能有相同名字的方法,这可能会引起混淆(用户可以通过 class 来创建自己的对象)。

More on Defining Functions

It is also possible to define functions with a variable number of arguments. There are three forms, which can be combined.

定义函数时可以设定可变数量的参数,这通常有三种方法并且互相可以组合使用。

Default Argument Values

The most useful form is to specify a default value for one or more arguments. This creates a function that can be called with fewer arguments than it is defined to allow. For example:

- 最经典的方法就是为函数的参数设定默认值。

def ask_ok(prompt, retries=4, reminder='Please try again!'):

while True:

reply = input(prompt)

if reply in {'y', 'ye', 'yes'}:

return True

if reply in {'n', 'no', 'nop', 'nope'}:

return False

retries = retries - 1

if retries < 0:

raise ValueError('invalid user response')

print(reminder)This function can be called in several ways:

- giving only the mandatory argument:

ask_ok('Do you really want to quit?') - giving one of the optional arguments:

ask_ok('OK to overwrite the file?', 2) - or even giving all arguments:

ask_ok('OK to overwrite the file?', 2, 'Come on, only yes or no!')

This example also introduces the in keyword. This tests whether or not a sequence contains a certain value.

in运算符用于检查列表中是否包含特定的值。

The default values are evaluated at the point of function definition in the defining scope, so that :

参数的默认值会在函数定义的那一刻固定,并作用于函数定义块中的语句。

i = 5

def f(arg=i):

print(arg)

i = 6

f()will print 5.

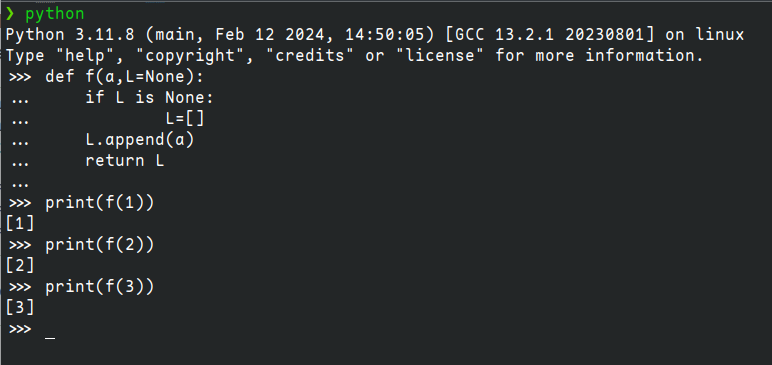

Important warning: The default value is evaluated only once. This makes a difference when the default is a mutable object such as a list, dictionary, or instances of most classes. For example, the following function accumulates the arguments passed to it on subsequent calls:

函数参数的默认值只会计算一次,因此如果默认值是可变的对象,例如列表、词典甚至大多数类的对象实例,那么结果可能不同。

def f(a, L=[]):

L.append(a)

return L

print(f(1))

print(f(2))

print(f(3))This will print :

[1]

[1, 2]

[1, 2, 3]

If you don’t want the default to be shared between subsequent calls, you can write the function like this instead:

如果不想在后续调用中共享默认值,那么应该像这样编写:

def f(a, L=None):

if L is None:

L = []

L.append(a)

return L

Keyword Arguments

Functions can also be called using keyword arguments6 of the form kwarg=value. For instance, the following function:

也可以使用

kwarg=value形式的关键字参数调用函数。例如,下面的函数

def parrot(voltage, state='a stiff', action='voom', type='Norwegian Blue'):

print("-- This parrot wouldn't", action, end=' ')

print("if you put", voltage, "volts through it.")

print("-- Lovely plumage, the", type)

print("-- It's", state, "!")accepts one required argument (voltage) and three optional arguments (state, action, and type). This function can be called in any of the following ways:

parrot(1000) # 1 positional argument

parrot(voltage=1000) # 1 keyword argument

parrot(voltage=1000000, action='VOOOOOM') # 2 keyword arguments

parrot(action='VOOOOOM', voltage=1000000) # 2 keyword arguments

parrot('a million', 'bereft of life', 'jump') # 3 positional arguments

parrot('a thousand', state='pushing up the daisies') # 1 positional, 1 keyword

but all the following calls would be invalid:

parrot() # required argument missing

parrot(voltage=5.0, 'dead') # non-keyword argument after a keyword argument

parrot(110, voltage=220) # duplicate value for the same argument

parrot(actor='John Cleese') # unknown keyword argument

In a function call, keyword arguments must follow positional arguments. All the keyword arguments passed must match one of the arguments accepted by the function (e.g. actor is not a valid argument for the parrot function), and their order is not important. This also includes non-optional arguments (e.g. parrot(voltage=1000) is valid too). No argument may receive a value more than once. Here’s an example that fails due to this restriction:

在函数调用中,关键字参数必须位于位置参数之后。

所有传递的关键字参数必须与函数接受的参数之一相匹配(例如,

actor不是parrot函数的有效参数),但是它们的顺序并不重要。这也包括非选项参数(例如,parrot(voltage=1000)也有效)。任何参数都不能多次接收一个值。下面是一个因这一限制而失败的例子:

>>> def function(a):

... pass

...

>>> function(0, a=0)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: function() got multiple values for argument 'a'When a final formal parameter of the form **name is present, it receives a dictionary (see Mapping Types — dict) containing all keyword arguments except for those corresponding to a formal parameter. This may be combined with a formal parameter of the form *name (described in the next subsection) which receives a tuple containing the positional arguments beyond the formal parameter list. (*name must occur before **name.) For example, if we define a function like this:

当出现

**name形式的最终形参时,它将接收一个字典,其中包含除与形参相对应的参数外的所有关键字参数。它可以与*name形式的形参结合使用,后者将接收一个元组,其中包含形参列表之外的位置参数(注意规则!*name必须在**name之前出现)。

def cheeseshop(kind, *arguments, **keywords):

print("-- Do you have any", kind, "?")

print("-- I'm sorry, we're all out of", kind)

for arg in arguments:

print(arg)

print("-" * 40)

for kw in keywords:

print(kw, ":", keywords[kw])It could be called like this:

cheeseshop("Limburger", "It's very runny, sir.",

"It's really very, VERY runny, sir.",

shopkeeper="Michael Palin",

client="John Cleese",

sketch="Cheese Shop Sketch")and of course it would print:

-- Do you have any Limburger ?

-- I'm sorry, we're all out of Limburger

It's very runny, sir.

It's really very, VERY runny, sir.

----------------------------------------

shopkeeper : Michael Palin

client : John Cleese

sketch : Cheese Shop SketchNote that the order in which the keyword arguments are printed is guaranteed to match the order in which they were provided in the function call.

请注意,打印关键字参数的顺序与函数调用中提供参数的顺序一致。

Special parameters

By default, arguments may be passed to a Python function either by position or explicitly by keyword. For readability and performance, it makes sense to restrict the way arguments can be passed so that a developer need only look at the function definition to determine if items are passed by position, by position or keyword, or by keyword.

默认情况下,参数可以按位置或显式地按关键字传递给 Python 函数。为了提高可读性和性能,限制参数的传递方式是有意义的,这样开发者只需查看函数定义,就能确定是通过位置传递、通过位置或关键字传递,还是通过关键字传递。

A function definition may look like:

def f(pos1, pos2, /, pos_or_kwd, *, kwd1, kwd2):

----------- ---------- ----------

| | |

| Positional or keyword |

| - Keyword only

-- Positional onlywhere / and * are optional. If used, these symbols indicate the kind of parameter by how the arguments may be passed to the function: positional-only, positional-or-keyword, and keyword-only. Keyword parameters are also referred to as named parameters.

上面的函数定义中

/和*是可选的,如果使用,这些符号表示参数的类型,即参数如何传递给函数——只通过位置、通过位置或关键字、只通过关键字。 关键字参数有时也称为 命名参数(named parameters,意为固定名称地传参)

Positional-or-Keyword Arguments

If / and * are not present in the function definition, arguments may be passed to a function by position or by keyword.

默认的方式,即如果

/和*没有显式地指出,那么参数就会通过位置或关键字的方式传递给函数。

Positional-Only Parameters

Looking at this in a bit more detail, it is possible to mark certain parameters as positional-only. If positional-only, the parameters’ order matters, and the parameters cannot be passed by keyword. Positional-only parameters are placed before a / (forward-slash). The / is used to logically separate the positional-only parameters from the rest of the parameters. If there is no / in the function definition, there are no positional-only parameters.

如果参数是仅通过位置传递的,那么参数摆放的位置就至关重要。仅通过位置传递的参数放置在

/符号之前,如果没有该符号,那么就不存在仅通过位置传递的参数。在

/符号之后的参数,可能是仅通过关键字传递,也可能是通过关键字或位置传递皆可的参数。

Parameters following the / may be positional-or-keyword or keyword-only.

Keyword-Only Arguments

To mark parameters as keyword-only, indicating the parameters must be passed by keyword argument, place an * in the arguments list just before the first keyword-only parameter.

要告知解释器该函数是仅通过关键字传递的,那么就应当将参数列表放置在

*符号之后。

Function Examples

Consider the following example function definitions paying close attention to the markers / and *:

>>> def standard_arg(arg):

... print(arg)

...

>>> def pos_only_arg(arg, /):

... print(arg)

...

>>> def kwd_only_arg(*, arg):

... print(arg)

...

>>> def combined_example(pos_only, /, standard, *, kwd_only):

... print(pos_only, standard, kwd_only)The first function definition, standard_arg, the most familiar form, places no restrictions on the calling convention and arguments may be passed by position or keyword:

>>> standard_arg(2)

2

>>> standard_arg(arg=2)

2

The second function pos_only_arg is restricted to only use positional parameters as there is a / in the function definition:

>>> pos_only_arg(1)

1

>>> pos_only_arg(arg=1)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: pos_only_arg() got some positional-only arguments passed as keyword arguments: 'arg'The third function kwd_only_args only allows keyword arguments as indicated by a * in the function definition:

>>> kwd_only_arg(3)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: kwd_only_arg() takes 0 positional arguments but 1 was given

>>> kwd_only_arg(arg=3)

3And the last uses all three calling conventions in the same function definition:

>>> combined_example(1, 2, 3)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: combined_example() takes 2 positional arguments but 3 were given

>>> combined_example(1, 2, kwd_only=3)

1 2 3

>>> combined_example(1, standard=2, kwd_only=3)

1 2 3

>>> combined_example(pos_only=1, standard=2, kwd_only=3)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: combined_example() got some positional-only arguments passed as keyword arguments: 'pos_only'Finally, consider this function definition which has a potential collision between the positional argument name and **kwds which has name as a key:

最后一个特殊情况,在下面的函数定义中,通过位置传递的参数

name和以name为键的**kwds之间可能会存在冲突。 (前文说到,**kwds是以字典作为参数,因此其中会有键值,这里讨论的问题就是前一个参数名和字典中键名混淆了)。

def foo(name, **kwds):

return 'name' in kwdsThere is no possible call that will make it return True as the keyword 'name' will always bind to the first parameter. For example:

由于关键字

'name'是字典传参的一个键,因此任何调用都会发生歧义,也就不会返回True。

>>> foo(1, **{'name': 2})

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: foo() got multiple values for argument 'name'

>>>But using / (positional only arguments), it is possible since it allows name as a positional argument and 'name' as a key in the keyword arguments:

但是如果使用

/规定好仅通过位置传递的参数,由于这允许name作为位置参数而'name'作为关键字参数的键,于是不会发生歧义。

>>> def foo(name, /, **kwds):

... return 'name' in kwds

...

>>> foo(1, **{'name': 2})

True

In other words, the names of positional-only parameters can be used in **kwds without ambiguity.

Recap

The use case will determine which parameters to use in the function definition:

def f(pos1, pos2, /, pos_or_kwd, *, kwd1, kwd2):

As guidance:

- Use positional-only if you want the name of the parameters to not be available to the user. This is useful when parameter names have no real meaning, if you want to enforce the order of the arguments when the function is called or if you need to take some positional parameters and arbitrary keywords.

如果不想让用户看到参数的名称,请使用 positional-only 的参数。当参数名称没有实际意义时,当需要在调用函数时强制执行参数顺序时,或者当需要使用某些位置参数和任意关键字时,这种方法非常有用。

- Use keyword-only when names have meaning and the function definition is more understandable by being explicit with names or you want to prevent users relying on the position of the argument being passed.

当名称具有意义,并且函数定义通过明确的名称更容易理解,或者希望避免用户依赖于所传递参数的位置时,请使用 keyword-only 参数。

- For an API, use positional-only to prevent breaking API changes if the parameter’s name is modified in the future.

对于 API,使用 positional-only 可防止在将来修改参数名称时破坏 API 的稳定性。

Arbitrary7 Argument Lists

Finally, the least frequently used option is to specify that a function can be called with an arbitrary number of arguments. These arguments will be wrapped up in a tuple (see Tuples and Sequences). Before the variable number of arguments, zero or more normal arguments may occur.

最后,最不常用的选项是指定函数可以用任意数量的参数调用。这些参数将封装在一个元组中(参见元组和序列)。在可变参数个数(的元组)之前,可能会出现零个或多个普通参数。

def write_multiple_items(file, separator, *args):

file.write(separator.join(args))Normally, these variadic arguments will be last in the list of formal parameters, because they scoop8 up all remaining input arguments that are passed to the function. Any formal parameters which occur after the *args parameter are ‘keyword-only’ arguments, meaning that they can only be used as keywords rather than positional arguments.

通常,这些可变数量参数会排在形参列表的最后,因为它们会占用传递给函数的所有剩余输入参数,而任何出现在

*args参数之后的形参都是 keyword-only 参数。

>>> def concat(*args, sep="/"):

... return sep.join(args)

...

>>> concat("earth", "mars", "venus")

'earth/mars/venus'

>>> concat("earth", "mars", "venus", sep=".")

'earth.mars.venus'Unpacking Argument Lists

The reverse situation occurs when the arguments are already in a list or tuple but need to be unpacked for a function call requiring separate positional arguments. For instance, the built-in range() function expects separate start and stop arguments. If they are not available separately, write the function call with the * -operator to unpack the arguments out of a list or tuple:

如果参数已经包含在 list 或 tuple 中,但若为需要单独位置参数的函数进行解包后传递时,就会发生特殊的情况:例如对内置函数

range需要 start 和 stop 两个位置参数,如果不能独立地从参数中获取,则需要利用*运算符进行解包:

>>> list(range(3, 6)) # normal call with separate arguments

[3, 4, 5]

>>> args = [3, 6]

>>> list(range(*args)) # call with arguments unpacked from a list

[3, 4, 5]In the same fashion, dictionaries can deliver keyword arguments with the ** -operator:

同样的风格,对于关键字参数,则需要

**运算符进行解包。

>>> def parrot(voltage, state='a stiff', action='voom'):

... print("-- This parrot wouldn't", action, end=' ')

... print("if you put", voltage, "volts through it.", end=' ')

... print("E's", state, "!")

...

>>> d = {"voltage": "four million", "state": "bleedin' demised", "action": "VOOM"}

>>> parrot(**d)

-- This parrot wouldn't VOOM if you put four million volts through it. E's bleedin' demised !Lambda Expressions

Small anonymous functions can be created with the lambda keyword. This function returns the sum of its two arguments: lambda a, b: a+b. Lambda functions can be used wherever function objects are required. They are syntactically restricted to a single expression. Semantically, they are just syntactic sugar for a normal function definition. Like nested function definitions, lambda functions can reference variables from the containing scope:

使用 lambda 关键字可以创建匿名函数。

- 例如:该函数返回两个参数之和:

lambda a, b: a+b。- 只要需要函数对象,就可以使用 lambda 函数。

- 它们在语法上仅限于单个表达式。

- 从语义上讲,它们只是普通函数定义的语法糖。

- 与嵌套函数定义一样,lambda 函数可以引用包含作用域的变量:

>>> def make_incrementor(n):

... return lambda x: x + n

...

>>> f = make_incrementor(42)

>>> f(0)

42

>>> f(1)

43The above example uses a lambda expression to return a function. Another use is to pass a small function as an argument:

上面的例子是使用 lambda 表达式返回函数运算的结果;另一种用法是作为参数传递给函数:

>>> pairs = [(1, 'one'), (2, 'two'), (3, 'three'), (4, 'four')]

>>> pairs.sort(key=lambda pair: pair[1])

>>> pairs

[(4, 'four'), (1, 'one'), (3, 'three'), (2, 'two')]Documentation Strings

Here are some conventions about the content and formatting of documentation strings.

下面是文档字符串的一些内容和规范。

The first line should always be a short, concise summary of the object’s purpose. For brevity, it should not explicitly state the object’s name or type, since these are available by other means (except if the name happens to be a verb describing a function’s operation). This line should begin with a capital letter and end with a period.

第一行应简明扼要地概述该对象的用途。为简洁起见,不应明确说明对象的名称或类型,因为这些内容可通过其他方式获得(除非名称恰好是描述函数操作的动词)。这一行应以大写字母开头,句号结尾。

If there are more lines in the documentation string, the second line should be blank, visually separating the summary from the rest of the description. The following lines should be one or more paragraphs describing the object’s calling conventions, its side effects, etc.

如果文档字符串的行数较多,则第二行应为空行,以便在视觉上将摘要与其余说明分开。下面几行应为一个或多个段落,描述对象的调用约定、副作用等。

The Python parser does not strip9 indentation from multi-line string literals in Python, so tools that process documentation have to strip indentation if desired. This is done using the following convention. The first non-blank line after the first line of the string determines the amount of indentation for the entire documentation string. (We can’t use the first line since it is generally adjacent to the string’s opening quotes so its indentation is not apparent in the string literal.) Whitespace “equivalent” to this indentation is then stripped from the start of all lines of the string. Lines that are indented less should not occur, but if they occur all their leading whitespace should be stripped. Equivalence of whitespace should be tested after expansion of tabs (to 8 spaces, normally).

Python 解析器不会对 Python 中的多行字符串常量进行缩进处理,因此处理文档的工具必须根据需要进行缩进处理。具体做法如下:

- 字符串第一行后的第一个非空行决定整个文档字符串的缩进量。(我们不能使用第一行,因为它通常与字符串开头的引号相邻,所以在字符串字面中它的缩进并不明显)

- 然后,从字符串所有行的开头去掉与该缩进“相当”的空白。

- 缩进较小的行不应出现,但如果出现,则应去除所有前导空白。

- 应在扩展制表符(通常为 8 个空格)后测试空白的等效性。

Here is an example of a multi-line docstring:

>>> def my_function():

... """Do nothing, but document it.

...

... No, really, it doesn't do anything.

... """

... pass

...

>>> print(my_function.__doc__)

Do nothing, but document it.

No, really, it doesn't do anything.Function Annotations

Function annotations are completely optional metadata information about the types used by user-defined functions (see PEP 3107 and PEP 484 for more information).

函数注解是关于用户定义函数所使用类型的可选的元数据信息。

Annotations are stored in the __annotations__ attribute of the function as a dictionary and have no effect on any other part of the function. Parameter annotations are defined by a colon after the parameter name, followed by an expression evaluating to the value of the annotation. Return annotations are defined by a literal ->, followed by an expression, between the parameter list and the colon denoting the end of the def statement. The following example has a required argument, an optional argument, and the return value annotated:

注解以字典形式存储在函数的

__annotations__属性中,对函数的其他部分没有影响。

- 参数注解的定义方法是在参数名称后加冒号,然后是一个表达式,该表达式的值就是注解的值

- 返回值注解的定义是在参数列表和表示

def语句结束的冒号之间用一个运算符->,然后是一个表达式。下面的示例注释了一个必选参数、一个可选参数和返回值:

>>> def f(ham: str, eggs: str = 'eggs') -> str:

... print("Annotations:", f.__annotations__)

... print("Arguments:", ham, eggs)

... return ham + ' and ' + eggs

...

>>> f('spam')

Annotations: {'ham': <class 'str'>, 'return': <class 'str'>, 'eggs': <class 'str'>}

Arguments: spam eggs

'spam and eggs'Intermezzo: Coding Style

Now that you are about to write longer, more complex pieces of Python, it is a good time to talk about coding style. Most languages can be written (or more concise, formatted) in different styles; some are more readable than others. Making it easy for others to read your code is always a good idea, and adopting a nice coding style helps tremendously for that.

For Python, PEP 8 has emerged as the style guide that most projects adhere to; it promotes a very readable and eye-pleasing coding style. Every Python developer should read it at some point; here are the most important points extracted for you:

-

Use 4-space indentation, and no tabs.

4 spaces are a good compromise between small indentation (allows greater nesting depth) and large indentation (easier to read). Tabs introduce confusion, and are best left out.

-

Wrap lines so that they don’t exceed 79 characters.

This helps users with small displays and makes it possible to have several code files side-by-side on larger displays.

-

Use blank lines to separate functions and classes, and larger blocks of code inside functions.

-

When possible, put comments on a line of their own.

-

Use docstrings.

-

Use spaces around operators and after commas, but not directly inside bracketing constructs:

a = f(1, 2) + g(3, 4). -

Name your classes and functions consistently; the convention is to use

UpperCamelCasefor classes andlowercase_with_underscoresfor functions and methods. Always useselfas the name for the first method argument (see A First Look at Classes for more on classes and methods). -

Don’t use fancy encodings if your code is meant to be used in international environments. Python’s default, UTF-8, or even plain ASCII work best in any case.

-

Likewise, don’t use non-ASCII characters in identifiers if there is only the slightest chance people speaking a different language will read or maintain the code.

Footnotes

-

意为“派上用场” ↩

-

意为“通配符” ↩

- ↩

-

Actually, call by object reference would be a better description, since if a mutable object is passed, the caller will see any changes the callee makes to it (items inserted into a list). ↩

-

属于 Python 自己为了效率而进行的优化,暂时不必管它。 ↩

-

什么是 keyword argument?根据文档的定义,指的是在函数调用中前面带有标识符(如

name=)的参数,或在字典中作为值传递的参数,前面带有**。例如复数计算函数complex()有这两种调用方式,其中的3和5都是关键字参数:complex(real=3, imag=5)或complex(**{'real': 3, 'imag': 5})↩ -

意为“任意的” ↩

-

scoop 本义为汤勺,scoop up 意为用勺子舀起,在这里引申为占用的空间。 ↩

-

本义为“除去”,“脱光”,这里引申为“处理” ↩